Operations vs Ownership vs HR Organizational Structures

Organizational structure drift causes issues

When your HR/Management org structure starts to drift from your operational and project development structure. The organization’s communication, shared understanding, system ownership, and incident response times suffer.

- Communication: meetings references teams that no longer exist, in terms of ownership of runtime systems and deliverables. Folks that should be in the room aren’t invited.

- Shared Understanding: If folks in different roles are referring to teams with different names which sometimes reference slightly different groups of people, understanding of who is working on which systems will become blurry.

- system ownership: running operations for a system and not having input into its long term ownership in direction leads to increased pages and incidents with no vision for a stable and coherent system.

- incident response: folks see incidents and can’t map the product feature and ownership to the system, team, and pager on-call / at fault to follow up on investigations

How org structure drift happens

If org charts, managers, and teams are reorged a few times eventually a newly formed team can inherit some legacy systems as it fits their newly defined mission. These inherited systems somehow have moved away from the original authors or recent operators. One day the company will find out that a critical system seems to be owned by a team totally unfamiliar with it, often during an incident. This poor outcome does clarify the issue of re-orgs that don’t reflect operation and code ownership responsibilities.

The tale of the teams from before…

In this tale, an incident occurs with various services having problems, this might be figured out by an outside team that leverages the service that has started to fail. It becomes clear this upstream service needs attention and that no one is clear who is responsible for the system… It hasn’t had updates for months, no deploys for weeks, the code owners file references a team that was reorged out of existence. During the incident the downstream team can even page that service’s owner to find that a responder knows nothing about the service and didn’t know it was assigned to their team… or that the service was inherited and only one person really knows anything about it and they are on vacation.

At this point during an incident, possibly in the middle of the night, you have folks with very little context about a system making decisions to “fix the service without safety” or “wake up people who likely don’t know how to help”. The failure of the moment must get resolved, and good people will dig in and figure it out, but during any good post-mortem (incident review). It should come up that there wasn’t clear ownership of that system.

- it wasn’t clear which product team owned the service

- or that team no longer actively worked on it, overlooked “legacy” system that is actually critical

- a team clearly owned it but knew nothing about it

- this was inherited after a reorg… none of the original engineers originally involved are involved anymore…

- The new team have spent only minimum maintenance efforts to keep it running.

- a eng team still clearly owned the service, but has been trying to deprecate it for years without enough support to make significant progress

- it actually isn’t clear who owns that any more… The team that owned it was re-orged away and it wasn’t noticed there is now a pager rotation with no people remaining.

If you have been around the block a few times you have likely seen unhealthy system maintenance before. It might happen slowly over time as teams come and go, without paying attention organizational structure drift has started to result in increased risk, increased burnout, lowered productivity.

What does organizational drift look like?

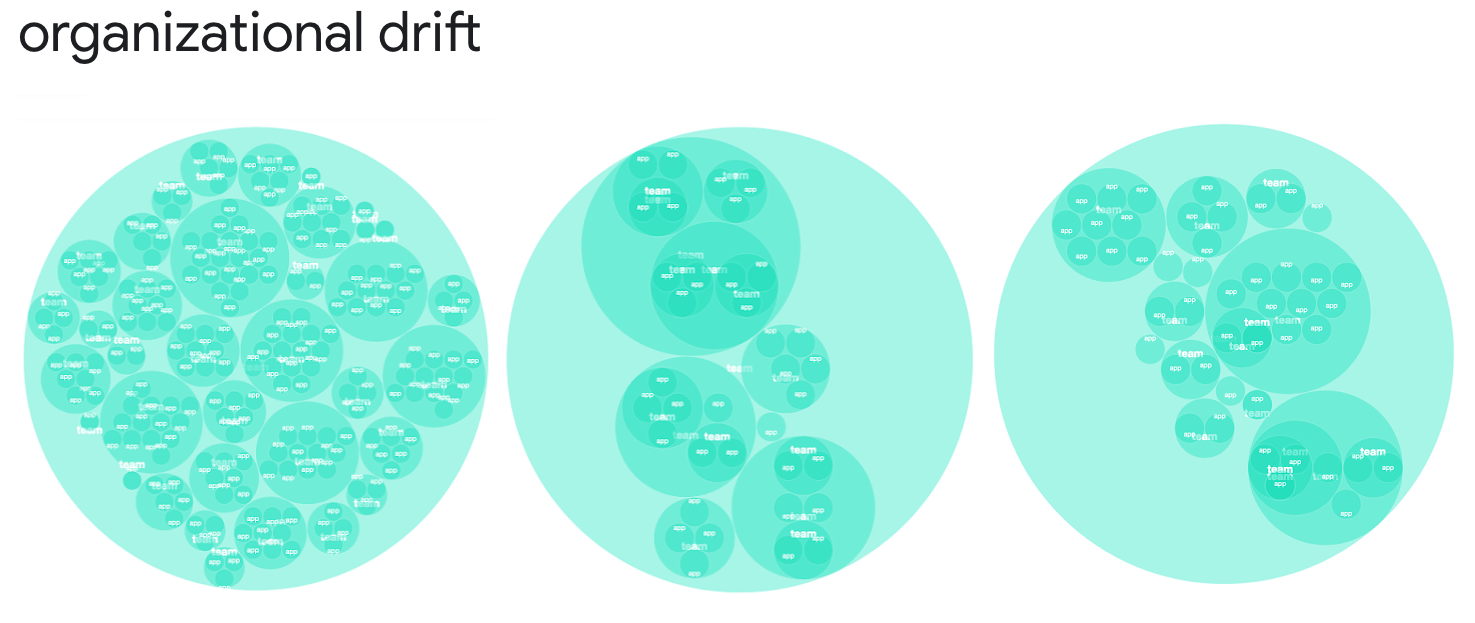

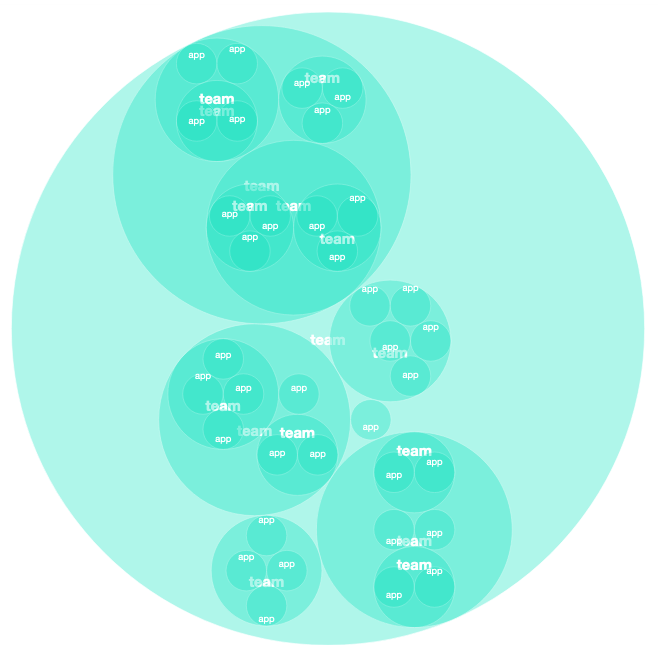

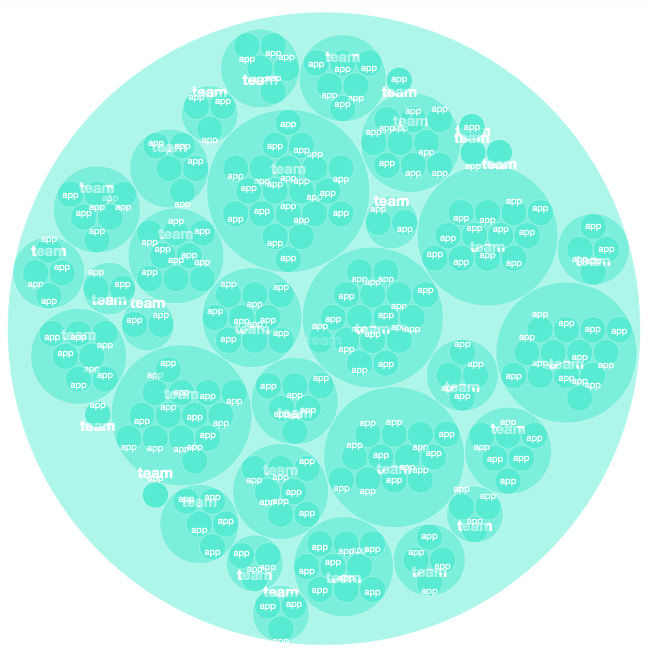

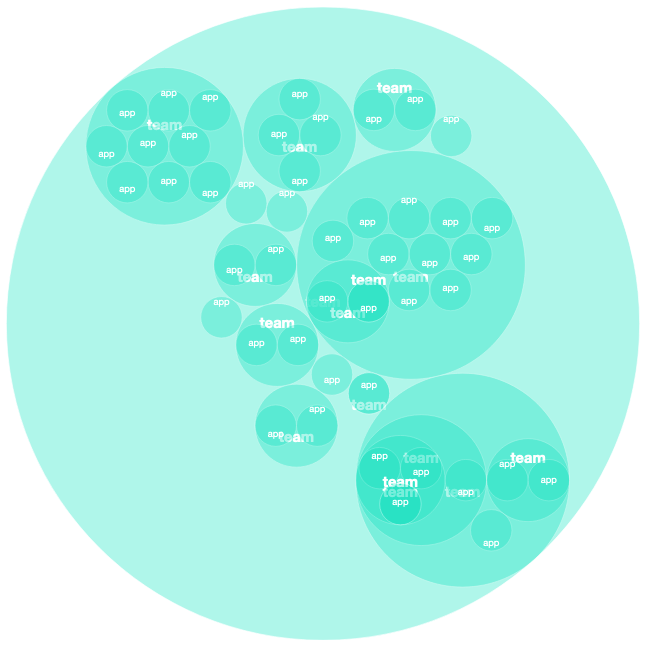

Depending on the current situationm needs folks end up having to try to use different tools and shared-language to find the right folks to help solve the problem. Below is some fake/scrubbed data based on Company Org charts mapping to apps, the PagerDuty teams mapped to apps, and Github teams mapped to apps (using CODEOWNERS files)

| Company Org Chart | PagerDuty Teams | Github Teams |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

diagrams showing the teams in terms of org charts, operations (PagerDuty), and code owners (Github)

Just from a visual check these diagrams diverge. When one starts to talk about the differences, various organizational issues become extremely obvious. From teams with far too many apps and responsibilities, to teams that simply do not exist anymore in terms of the org chart, but have sets of employees maintaining legacy systems in terms of code ownership or operational support.

These diagrams don’t even cover that we have Eng Org team charts which don’t 1:1 align to the Product Org charts. If there is an incident occurring for say a 3rd party payment in an international market, that hasn’t triggered pager alerts… Where would you look for support? The International Expansion Engineering team? The Product person in the chart of payment flows? The Engineering Payments team? What if the payment issues are only for a certain product feature? Even if you know the specific application that has the code in it, do you reach out to the operation support team or the code owners of the system?

How many different ways do folks try to interact with a team?

The value in having teams with consistent naming across multiple views makes it easier to find the right team whether it is for customer support, an active incident, or possibly just project collaboration or questions. There are many lenses where clear lines to or from teams can be helpful.

- customer relations support: user voice queue

- pagers / on-call: pager-duty

- code owners: github

- metric owners: Datadog, can we map to services or teams?

- real-time discussions: Slack, which channel for the team? or a project channel?

How to fix it…

Everyone wants a data driven business and often can’t even get their organizational data to align across systems. Having a source of truth and being able to map it to any and all different use cases as views of the data is a powerful idea. Management should try to keep those views of teams as close as possible and have good reasons for when they drift (migrating from a out-dated to new view of responsibilities as an example). Companies need to make it very easy to find and look up the team organizational information and fix discrepancies.

The fix is aligning on a source of truth and restructuring the other mappings to follow. You can start to enforce all other systems to map back to the source off truth in order of importance. Do this in code or an automated process, flag mis-matches, do not only rely on humans or you be back at it again as it quickly falls out of sync.

When a company has shared views of what teams exist, who is on those teams, and what they are working on we can start to use data to look at ensuring product and system goals have appropriate staffing to support the goals, and we can see and respond to changes in the organization such as sudden unexpected resignations putting critical systems at risk. I will talk more about how we can look at team and service health in future postings.