Ruby Caches - Rails Cache Network Requests

A series of posts will explore and detail some of the current Rails caching code. This post takes a deeper look at the network requests involved in caching.

These posts attempt to explain in more detail, but please do read the official Rails Caching Guide docs, which are also very good.

Rails Cache Posts:

- Rails Cache Initialization

- Rails Cache Comparisons

- Rails Cache Workflows

- Rails Cache Network Requests

Rails Cache Network Requests

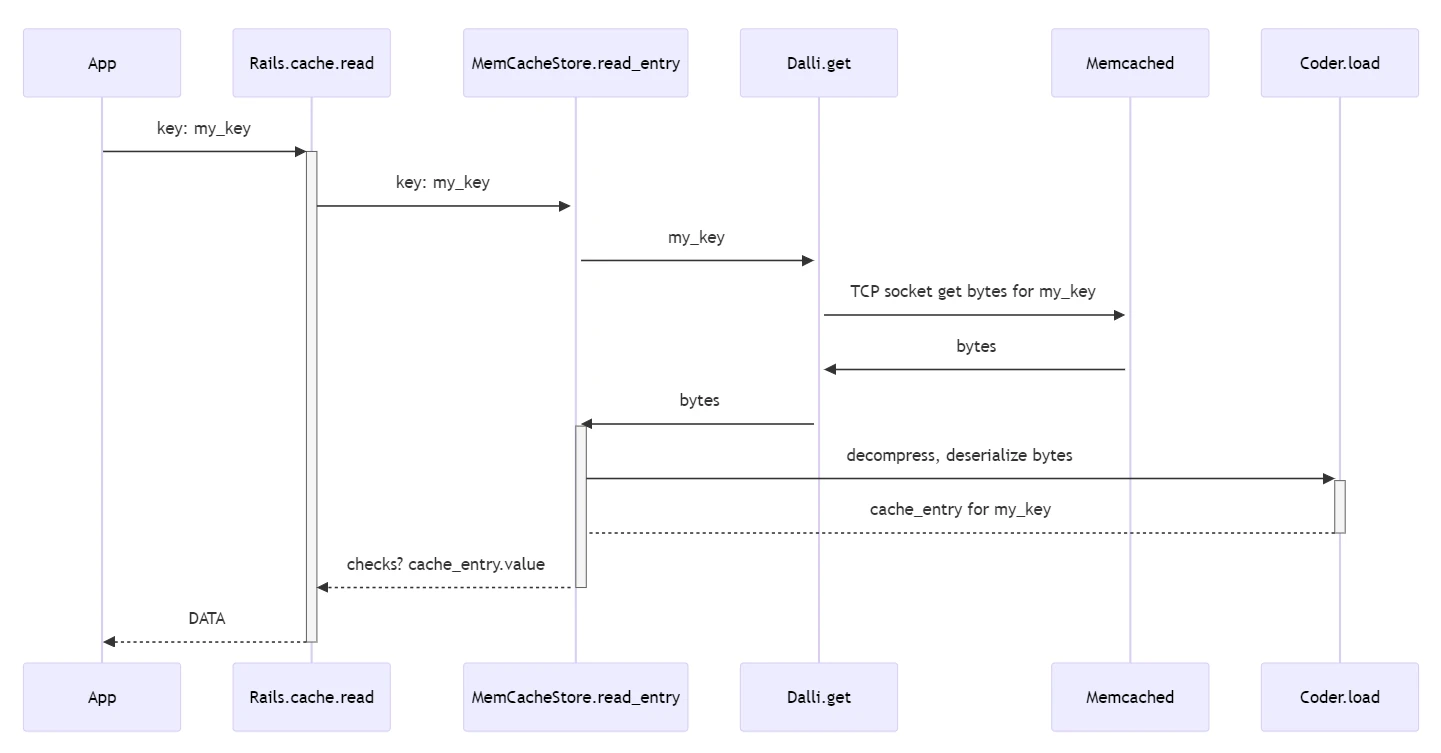

Most of the larger Rails applications end up using a cache server that is accessed over the network. This is because many of the simpler caches, like filestore and memory, do not work for a horizontally scaling Rails deployment. In contrast, you can set up a localhost Redis or Memcached server, which is generally just for development or small-scale applications. Let’s look at what happens with a typical Rails cache configured with a memcached server.

Let’s not look at serialization or compression but at what is going on to get data over the network.

Rails Cache Network Calls

In the previous post, Rails cache workflows, we covered how a Rails.cache.read will make a network request to the memcached Server to get the data.

Rails.cache.write("key", "my cached value")

result = Rails.cache.read("key")

puts result

=> "my cached value"

The Rails.cache.read call will use the Dalli Ruby client to request data from a Memcached server. What does that look like? Let’s look at the code to use Dalli directly to better understand what is happening. The Rails memcached store just provides helpers for working with Dalli.

dalli_key = "dalli_key"

dalli = Dalli::Client.new('localhost:11211')

dalli.set(dalli_key, "my cached value")

result = dalli.get(dalli_key)

puts result

=> "my cached value"

Usually, when interacting with a cache, you will use Rails.cache; outside of Rails, you might use Dalli (or Redis) directly. While these gems are great, it is good to know that they are simple network clients under the hood. For example, instead of using Dalli, we could do all of this with far less robust error handling (IE don’t use this code in production). Hopefully, this shows the layers of abstraction between Rails, the underlying caching library, and the Ruby code used to make network requests. Each layer of abstraction adds value and convience, but understanding all the layers can be helpful. For example, when you want to help performance optimize something, knowing which layer is slowing things down can be helpful.

sock = TCPSocket.new('127.0.0.1', '11211', connect_timeout: 1)

sock.setsockopt(Socket::IPPROTO_TCP, Socket::TCP_NODELAY, true)

sock.setsockopt(Socket::SOL_SOCKET, Socket::SO_KEEPALIVE, true)

# set a cache value via a raw socket

sock.write("set sock_key 0 3600 15\r\n")

sock.write("my cached value")

sock.write("\r\n")

sock.flush

sock.readline # clear the buffer

# read a cache value via a raw socket

sock.write("get sock_key\r\n")

sock.readline

result = sock.read(15)

puts result

=> "my cached value"

Caches and Network Failures

Simple enough, but as with anything over the network, what happens if the network goes down?

dalli.get("dalli_key")

=> No server available (Dalli::RingError)

That isn’t good; we can’t have trying to use a cache raise exceptions on misses. Well, Rails actually doesn’t. While it uses Dalli under the hood, it has a nicer API that helps avoid things like that.

Rails.cache.read("some_non_existing_key")

=> nil

A miss for a key not found in the cache and a miss because the cache was down will both return nil. So, the Rails.cache API makes it a little simpler to work with network errors. It is still worth considering how your code handles these errors. You often don’t want a nil but instead want to get the data from a different source.

Testing Network Errors with Toxiproxy

OK, we don’t want errors. How do we test what our code will do and how to handle it properly? There are several ways to test network error conditions, but one I like to use is toxiproxy. It can simulate network and system conditions for chaos and resiliency testing, making it easy to test things like the endpoint has gone down.

You can read the toxiproxy ruby docs for instructions on how to get started, but the example code below should provide the basics.

# add to Gemfile

gem "toxiproxy"

Also, update your test_helper.rb

Toxiproxy.populate([{

name: "memcached",

listen: "localhost:11222",

upstream: "localhost:11211",

}])

Then you can add toxiproxy code to any of your tests, in this case, to target what happens when memcached isn’t available.

# in book.rb

def save_to_cache

Rails.cache.write(Book.key_for_id(id), self, ttl: 600)

end

def self.get_from_cache(id)

Rails.cache.read(key_for_id(id))

end

def self.key_for_id(id)

"Model.book.#{id}"

end

# in book_test.rb

test "uses cache get" do

@book.save!

@book.save_to_cache

assert_equal(@book, Book.get_from_cache(@book.id))

# Note: toxi proxy is not parallel test safe

Toxiproxy[/memcached/].down do

assert_equal(nil, Book.get_from_cache(@book.id))

end

end

The test above makes it easy to see that the Rails cache won’t raise and will just return nil

The example above also shows why you don’t often see a Rails.cache.read in isolation. I often use Rails.cache.fetch. Let’s add some code and write a test to see how that works.

# in book.rb

def self.fetch_from_cache(id)

Rails.cache.fetch(key_for_id(id)) { Book.find(id) }

end

# in book_test.rb

test "uses db on cache fetch failure" do

@book.save!

@book.save_to_cache

assert_equal(@book, Book.get_from_cache(@book.id))

# toxi proxy is not parallel test safe

Toxiproxy[/memcached/].down do

assert_equal(@book, Book.fetch_from_cache(@book.id))

end

end

In this case, you can see that using Rails.cache.fetch will more cleanly handle any network issues to your cache server. It also makes it easy to implement read-through caching on any query.

Cache Request Details

While I have some other details I want to get into with Toxiproxy, and how to optimize caching code. This post has gotten long enough, in this post we dug through all the layers and exposed some of the details, and also showed some tooling that can help test and verify network failure conditions. We can build on this further in the next time.