Ownership in an age of microservices

This is the second post in a series about organization structures, teams and ownership, and application health.

Ownership challenges abound in microservices

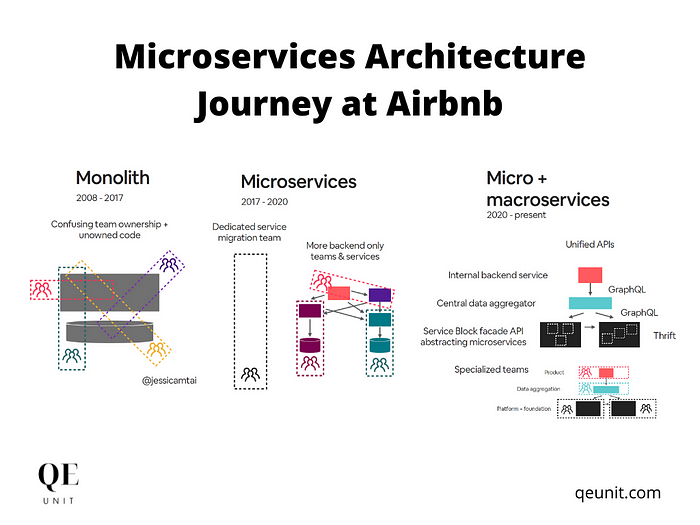

While there are many great resources out there that discuss microservices, where they may or may not be a good fit, and how some companies have decided to move away from them, and back to a monolith, in this post I am going to focus on some of the unique challenges that microservices present with regard to ownership. Ownership is frequently called out as a common problem with microservices, and both Uber, working towards macro-services with a Domain-Oriented Microservice Architecture, and AirBnb’s journey towards macro-service Domain aggregation are aimed at improving the clarity of ownership of domains of data and the teams and services that support them.

Microservices and evolving models of ownership

There are many different models of ownership, and one of the reasons microservices took off was to avoid the “tragedy of the commons” problem that often occurs in large shared codebases. We break the systems apart in an attempt to avoid shared codebases that tend to degrade over time. As companies moved to many smaller systems, a number of different ownership models emerged:

- Single person owner

- Orphan codebase, due to attrition or team re-assignment

- Modular Monolith, shared ownership, whether clear or unclear

- Team Ownership (my preferred)

- Workgroup/Guild/Steering Committee Ownership

With these came some more modern code collaboration patterns, such as

- Internal tickets

- Internal open-source (my preferred)

- Trusted outsider

- Tour of duty

- Embedded expert

These are all explained very well in a post patterns of cross-team collaboration. I personally like team ownership, acting as stewards of the long term vision and domain of services, and influencing changes via an internal open-source model. The team, in this model, plays a similar role to that of the primary contributors in an open source project.

Strong ownership takes time

In a decomposed, microservices ecosystem I personally believe that having a team with a long history of knowledge-building and maintaining an app will lead to better outcomes. The institutional knowledge of operating the service feeds back into the development practices of the team. Over time, the team learns how to mitigate risk, anticipate needs, and more quickly and flexibly change and evolve the system. Strong team ownership also helps with communication, especially during incident response as everyone knows which team owns a given app, which adds confidence that the team also has deep knowledge of the system and will be able to support it. A stable relationship between business domain, services, and team brings clarity and shared knowledge of where responsibilities and vision for the domain belongs. In my last post, I will discuss how reorgs and diverging team names across systems causes organizational drift and confusion.

Who is responsible for the Distributed Monolith?

One issue that comes up in microservices is the emergence of a distributed monolith. As microservices have been around for a fairly long time at this point (in tech life cycles that is) there are places that have “legacy” microservice systems, perhaps better described as a distributed monolith. As a company first splits up a legacy monolith, they often make many learning mistakes, like setting up poor system boundaries which leads to distributed transactions, or taking shortcuts, like giving multiple applications read/write access to a single shared database (hello shared DB, my old friend). The early extracted set of services often have some “winners” that prove the value of a well-defined and executed extraction, as well as some less than ideal systems that become part of the distributed monolith, the remains of the legacy monolith that folks have failed to finish extracting. At some point, companies need to refactor, delete, and reduce the maintenance of microservices the same way companies end up building strategies to unravel or modernize legacy monoliths, via Modular Monolith and other techniques.

The problem with poorly extracted and tightly coupled services is that they don’t have clear domain boundaries, which makes it difficult to build strong ownership and knowledge around. These services end up with the same tragedy of the commons issues of a large, shared code base.

As part of any thinking about reorgs, considering these systems is key. The new structure should have clear domain boundaries, and take future ownership of these systems into account. A steering group, architects, or your senior ICs can help think through high-friction boundaries and make recommendations. Often, I see companies try to reorg while only thinking about the new work, as opposed to taking into account these hard to maintain poorly understood systems. This creates a lot of technical drag on the team(s) trying to own them, as well as on any team that owns a feature that is yet to be extracted from these systems. If the reorg doesn’t take this into account, it might make the situation worse by trying to brush these problem areas under a rug.

Reorgs and technology investments to help address confusing ownership at Airbnb

Reorgs impact clear ownership

At the same time, companies are also very keen on reorgs, in part due to the recent popularity of the inverse conway maneuver. This attempts to use the fact that with Conway’s law, particularly in microservices, your org structure ends up designing your architecture, at least in terms of system boundaries. The Team Topologies book about this is very compelling, but I think many organizations attempt it without fully understanding the domains and systems that teams currently own. Without a process to understand and purposefully move applications to proper owning teams, the reorg can end up causing more chaos and confusion, increasing maintenance costs, and lowering MTTR for critical user journeys, not to mention reducing trust within the org. When done well, a reorg can lead to stronger and better understood domains owned by teams with a coherent set of domain and system boundaries. This leads to strong ownership and deeper domain knowledge within the team, enabling them to be more productive and responsive to the needs of the business.

When the company needs to freeze hiring or contract, how are legacy systems assigned ownership and supported. Reorging when a company is growing leads to more positive ownership opportunities than reorging when a company is at a stable size or shrinking. How do we set up ownership so that we can withstand ups and downs. –Erica Tripp

As leadership sees some of the issues falling out of the current org structures, they often will reach for the reorg, but reorgs themselves don’t change the ways of working, and often can make maintaining legacy systems harder if you move folks away from areas they have built domain expertise.

changing structure and process without addressing leadership, cultural and ways of working issues, usually exacerbates existing problems rather than improving performance. –The Structure and Process Fallacy

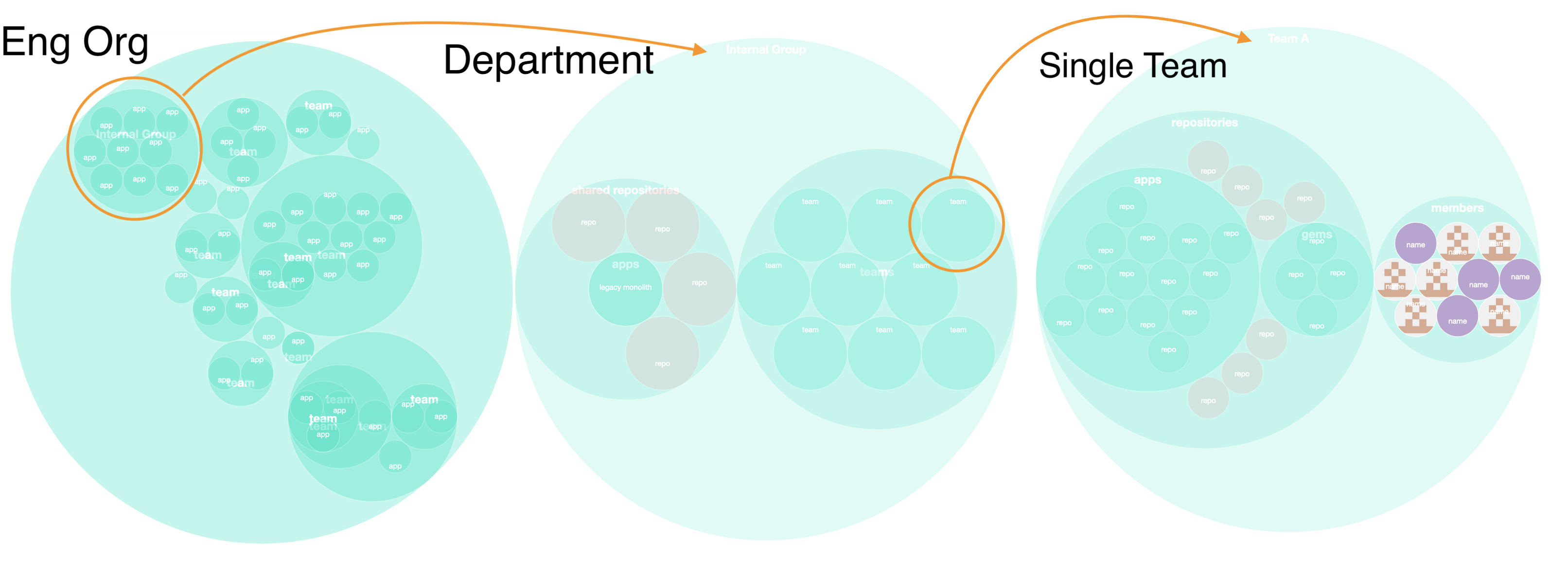

In terms of clear ownership in microservices some even propose that, “Ideally each team has only one service”. If you are a growing company that has been evolving microservices, I doubt this is the situation. After a number of reorgs, and folks coming and going, a team’s responsibilities more often look like a giant group of only semi-related services and libraries.

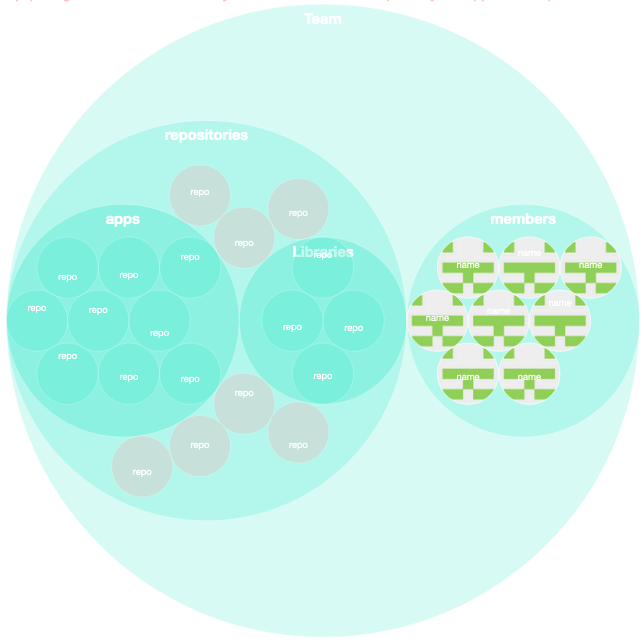

A overloaded but not entirely uncommon diagram showing a teams repo ownership

If you end up having teams with ownership responsibilities as shown above, with more services than team members, it is unlikely there is strong ownership with deep understanding of all the systems involved.

What do we need to know about our teams?

We need to better understand the reality of what our teams are working on and if they are supported to work on the goals we set out for them. If the team’s goals align with the systems they have, if they are set up for success or are in a declining spiral of more maintenance than they can healthily support while also delivering new value. There is a lot we should know about how our teams currently look, so that we can re-balance in ways that ensure all teams are healthier and more effective. While we need to also consider domains, specific systems, and team’s charters to re-define an org structure, there are a lot of things that should be considered about the team health directly.

- Is the team overloaded?

- Do they maintain too many repos for the number of folks on the team?

- Do they have too many weeks on-call per developer?

- Are they supporting legacy systems with high maintenance burdens, or all newer and actively supported systems?

- Are the systems they support well bound to a coherent set of domains?

- Are the apps they currently support healthy? (I will dig in more into what is a healthy app in a future post).

- Is the team well rounded?

- Does the team have some tenured folks that can navigate the org and have historical context?

- Is the team a good mix of Sr / Jr folks, for the type or work?

- Is the manager a good fit for the team (A newish manager with a Jr and non-tenured team, leaves everyone trying to learn and navigate at the same time)

- How is attrition impacting the team?

- Teams with higher attrition than others are likely significantly impaired, consider what really happens when someone leaves a team

What do we need to know about our repos and apps?

We can’t just talk about teams without looking at the details. At some point we want to also look at all the repos they own, what they most actively work on, and the health of those systems. Especially after several rounds of reorgs, teams often end up with some things that don’t fit well into their charter, but responsibility for a system has to end up somewhere. It is best to at least make it clear where the responsibility ends up, even if it immediately requires some discussion about how the legacy load might not be healthy, so that it can be addressed. I will follow up on this question in a future post, digging into how to think about the health of repos and the value and risk they create for companies.

Strong ownership drives quality

There are many other posts talking about the impacts on ownership of microservices. I think there are still a lot of good questions on how best to handle it. I am mostly trying to make the case that thinking through the domain boundaries is not enough, one has to think of what it takes to have deep knowledge and strong ownership of a domain. It takes having a healthy team that isn’t spread too thin. Ideally they have a cohesive set of services and responsibilities that form a common domain. If you move teams into what seems like better domains as part of a reorg but don’t look at or address the other responsibilities a team may already have, strong ownership and the attempts at more clarity of domains will not succeed.